d

Keeping green

Your main branch of the code should always remain green. Being green means that all the steps of your build pipeline should complete successfully: the project should build successfully, tests should run without errors, and the linter shouldn't have anything to complain about, etc.

Why is this important? You will likely deploy your code to production specifically from your main branch. Any failures in the main branch would mean that new features cannot be deployed to production until the issue is sorted out. Sometimes you will discover a nasty bug in production that was not caught by the CI/CD pipeline. In these cases, you want to be able to roll the production environment back to a previous commit in a safe manner.

How do you keep your main branch green then? Avoid committing any changes directly to the main branch. Instead, commit your code on a branch based on the freshest possible version of the main branch. Once you think the branch is ready to be merged into the main you create a GitHub Pull Request (also referred to as PR).

Working with Pull Requests

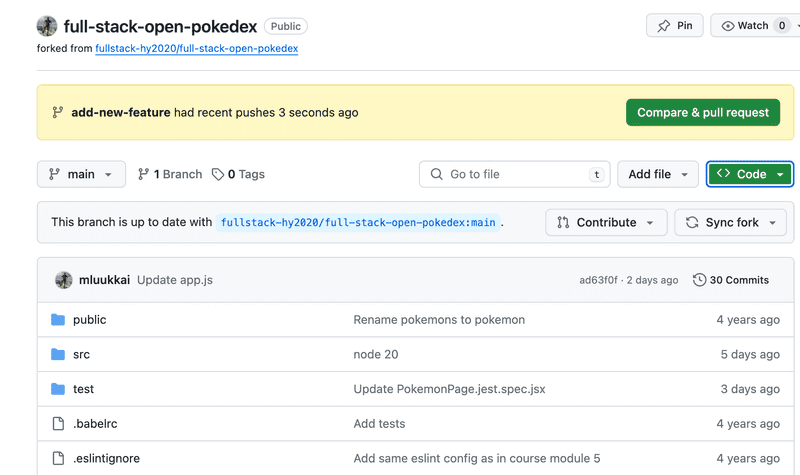

Pull requests are a core part of the collaboration process when working on any software project with at least two contributors. When making changes to a project you checkout a new branch locally, make and commit your changes, push the branch to the remote repository (in our case to GitHub) and create a pull request for someone to review your changes before those can be merged into the main branch.

There are several reasons why using pull requests and getting your code reviewed by at least one other person is always a good idea.

- Even a seasoned developer can often overlook some issues in their code: we all know of the tunnel vision effect.

- A reviewer can have a different perspective and offer a different point of view.

- After reading through your changes, at least one other developer will be familiar with the changes you've made.

- Using PRs allows you to automatically run all tasks in your CI pipeline before the code gets to the main branch. GitHub Actions provides a trigger for pull requests.

You can configure your GitHub repository in such a way that pull requests cannot be merged until they are approved.

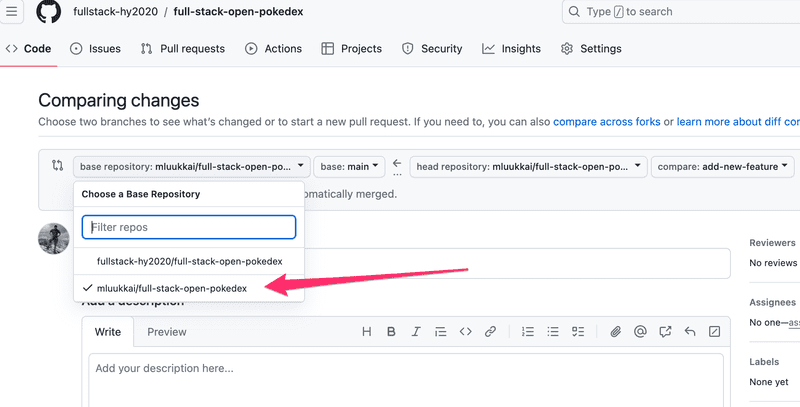

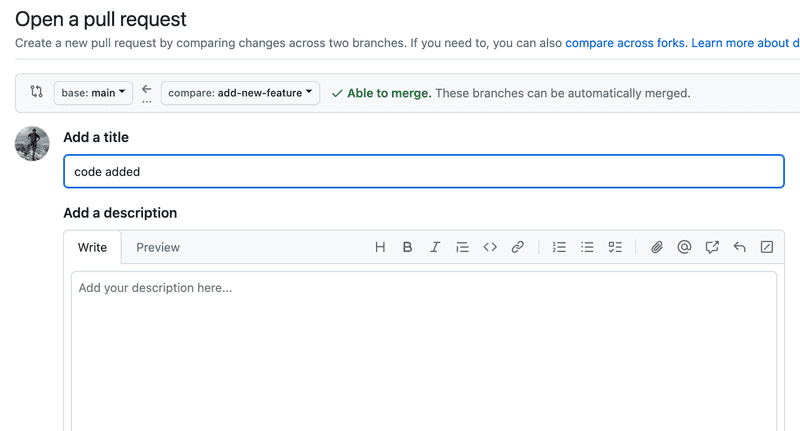

To open a new pull request, open your branch in GitHub and click on the green "Compare & pull request" button at the top. You will be presented with a form where you can fill in the pull request description.

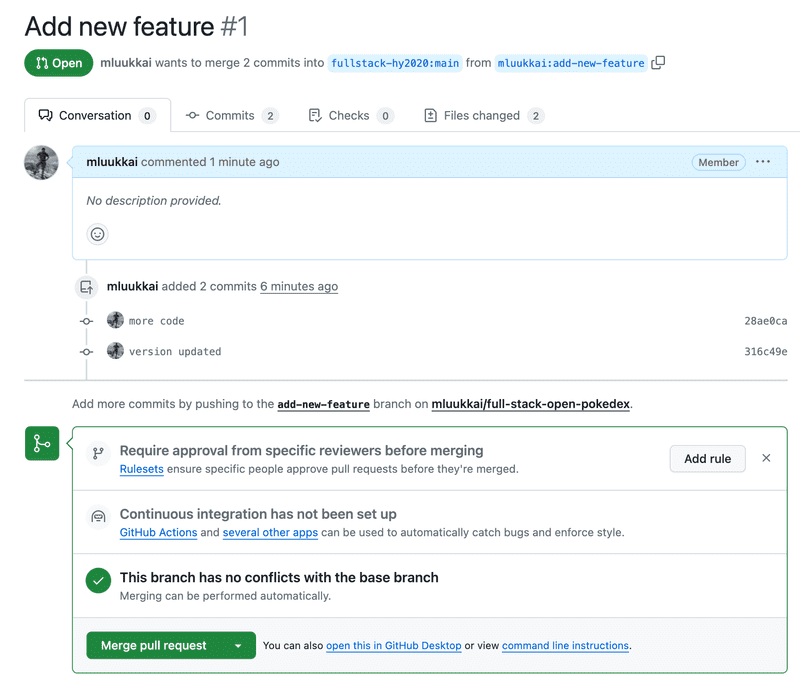

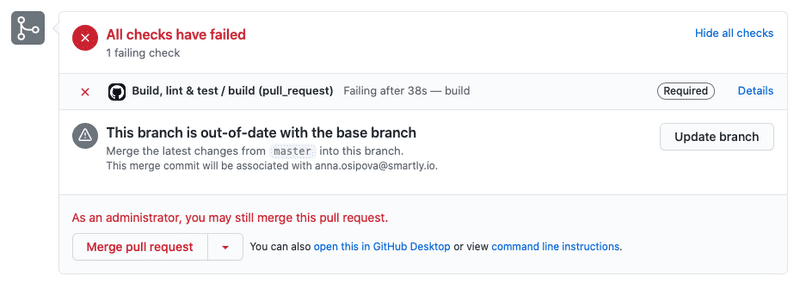

GitHub's pull request interface presents a description and the discussion interface. At the bottom, it displays all the CI checks (in our case each of our Github Actions) that are configured to run for each PR and the statuses of these checks. A green board is what you aim for! You can click on Details of each check to view details and run logs.

All the workflows we looked at so far were triggered by commits to the main branch. To make the workflow run for each pull request we would have to update the trigger part of the workflow. We use the "pull_request" trigger for branch "main" (our main branch) and limit the trigger to events "opened" and "synchronize". Basically, this means, that the workflow will run when a PR into the main branch is opened or updated.

So let us change events that trigger of the workflow as follows:

on:

push:

branches:

- main

pull_request: branches: [main] types: [opened, synchronize]We shall soon make it impossible to push the code directly to the main branch, but in the meantime, let us still run the workflow also for all the possible direct pushes to the main branch.

Versioning

The most important purpose of versioning is to uniquely identify the software we're running and the code associated with it.

The ordering of versions is also an important piece of information. For example, if the current release has broken critical functionality and we need to identify the previous version of the software so that we can roll back the release back to a stable state.

Semantic Versioning and Hash Versioning

How an application is versioned is sometimes called a versioning strategy. We'll look at and compare two such strategies.

The first one is semantic versioning, where a version is in the form {major}.{minor}.{patch}. For example, if the version is 1.2.3, it has 1 as the major version, 2 is the minor version, and 3 is the patch version.

In general, changes that fix the functionality without changing how the application works from the outside are patch changes, changes that make small changes to functionality (as viewed from the outside) are minor changes and changes that completely change the application (or major functionality changes) are major changes. The definitions of each of these terms can vary from project to project.

For example, npm-libraries are following the semantic versioning. At the time of writing this text (16th March 2023) the most recent version of React is 18.2.0, so the major version is 18 and the minor version is 2.

Hash versioning (also sometimes known as SHA versioning) is quite different. The version "number" in hash versioning is a hash (that looks like a random string) derived from the contents of the repository and the changes introduced in the commit that created the version. In Git, this is already done for you as the commit hash that is unique for any change set.

Hash versioning is almost always used in conjunction with automation. It's a pain (and error-prone) to copy 32 character long version numbers around to make sure that everything is correctly deployed.

But what does the version point to?

Determining what code belongs to a given version is important and the way this is achieved is again quite different between semantic and hash versioning. In hash versioning (at least in Git) it's as simple as looking up the commit based on the hash. This will let us know exactly what code is deployed with a specific version.

It's a little more complicated when using semantic versioning and there are several ways to approach the problem. These boil down to three possible approaches: something in the code itself, something in the repo or repo metadata, something completely outside the repo.

While we won't cover the last option on the list (since that's a rabbit hole all on its own), it's worth mentioning that this can be as simple as a spreadsheet that lists the Semantic Version and the commit it points to.

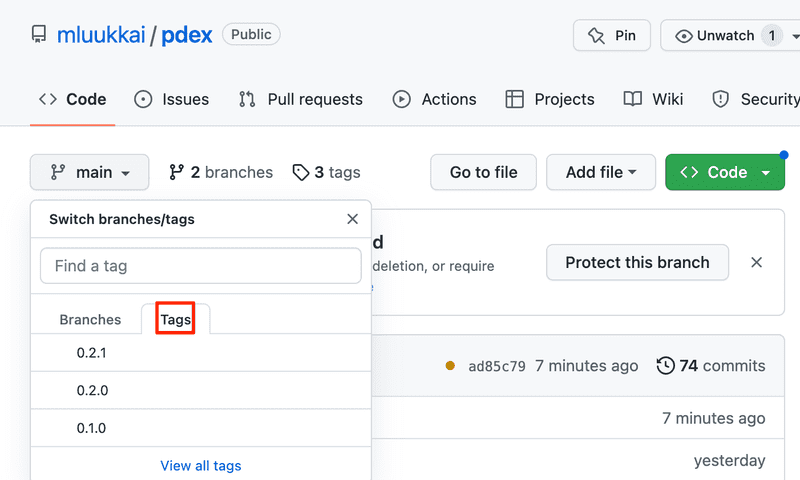

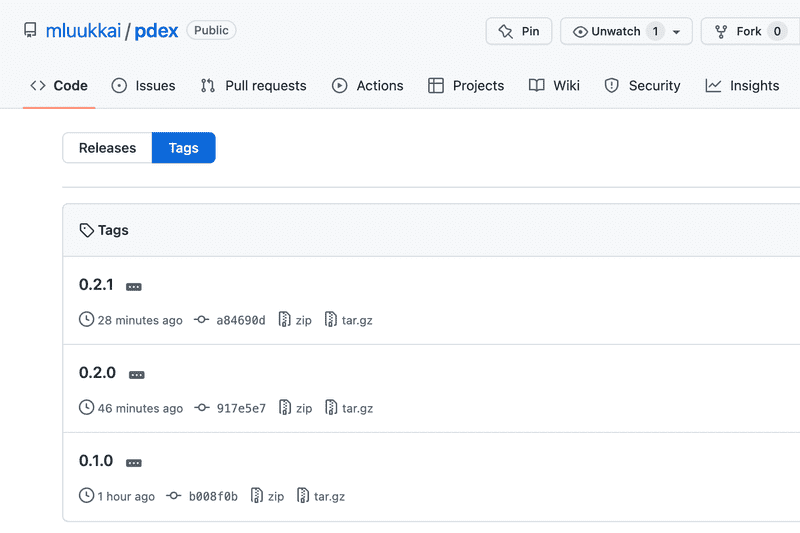

For the two repository based approaches, the approach with something in the code usually boils down to a version number in a file and the repo/metadata approach usually relies on tags or (in the case of GitHub) releases. In the case of tags or releases, this is relatively simple, the tag or release points to a commit, the code in that commit is the code in the release.

Version order

In semantic versioning, even if we have version bumps of different types (major, minor, or patch) it's still quite easy to put the releases in order: 1.3.7 comes before 2.0.0 which itself comes before 2.1.5 which comes before 2.2.0. A list of releases (conveniently provided by a package manager or GitHub) is still needed to know what the last version is but it's easier to look at that list and discuss it: It's easier to say "We need to roll back to 3.2.4" than to try communicate a hash in person.

That's not to say that hashes are inconvenient: if you know which commit caused the particular problem, it's easy enough to look back through a Git history and get the hash of the previous commit. But if you have two hashes, say d052aa41edfb4a7671c974c5901f4abe1c2db071 and 12c6f6738a18154cb1cef7cf0607a681f72eaff3, you really can not say which came earlier in history, you need something more, such as the Git log that reveals the ordering.

Comparing the Two

We've already touched on some of the advantages and disadvantages of the two versioning methods discussed above but it's perhaps useful to address where they'd each likely be used.

Semantic Versioning works well when deploying services where the version number could be of significance or might actually be looked at. As an example, think of the JavaScript libraries that you're using. If you're using version 3.4.6 of a particular library, and there's an update available to 3.4.8, if the library uses semantic versioning, you could (hopefully) safely assume that you're ok to upgrade without breaking anything. If the version jumps to 4.0.1 then maybe it's not such a safe upgrade.

Hash versioning is very useful where most commits are being built into artifacts (e.g. runnable binaries or Docker images) that are themselves uploaded or stored. As an example, if your testing requires building your package into an artifact, uploading it to a server, and running tests against it, it would be convenient to have hash versioning as it would prevent accidents.

As an example think that you're working on version 3.2.2 and you have a failing test, you fix the failure and push the commit but as you're working in your branch, you're not going to update the version number. Without hash versioning, the artifact name may not change. If there's an error in uploading the artifact, maybe the tests run again with the older artifact (since it's still there and has the same name) and you get the wrong test results. If the artifact is versioned with the hash, then the version number must change on every commit and this means that if the upload fails, there will be an error since the artifact you told the tests to run against does not exist.

Having an error happen when something goes wrong is almost always preferable to having a problem silently ignored in CI.

Best of Both Worlds

From the comparison above, it would seem that the semantic versioning makes sense for releasing software while hash-based versioning (or artifact naming) makes more sense during development. This doesn't necessarily cause a conflict.

Think of it this way: versioning boils down to a technique that points to a specific commit and says "We'll give this point a name, it's name will be 3.5.5". Nothing is preventing us from also referring to the same commit by its hash.

There is a catch. We discussed at the beginning of this part that we always have to know exactly what is happening with our code, for example, we need to be sure that we have tested the code we want to deploy. Having two parallel versioning (or naming) conventions can make this a little more difficult.

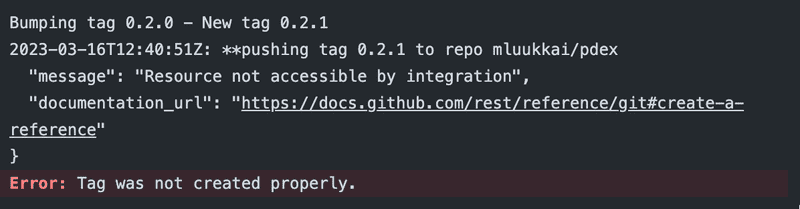

For example, when we have a project that uses hash-based artifact builds for testing, it's always possible to track the result of every build, lint, and test to a specific commit and developers know the state their code is in. This is all automated and transparent to the developers. They never need to be aware of the fact that the CI system is using the commit hash underneath to name build and test artifacts. When the developers merge their code to the main branch, again the CI takes over. This time, it will build and test all the code and give it a semantic version number all in one go. It attaches the version number to the relevant commit with a Git tag.

In the case above, the software we release is tested because the CI system makes sure that tests are run on the code it is about to tag. It would not be incorrect to say that the project uses semantic versioning and simply ignore that the CI system tests individual developer branches/PRs with a hash-based naming system. We do this because the version we care about (the one that is released) is given a semantic version.

A note about using third-party actions

When using a third-party action such that github-tag-action it might be a good idea to specify the used version with hash instead of using a version number. The reason for this is that the version number, that is implemented with a Git tag can in principle be moved. So today's version 1.61.0 might be a different code that is at next week the version 1.61.0!

However, the code in a commit with a particular hash does not change in any circumstances, so if we want to be 100% sure about the code we use, it is safest to use the hash.

Version 1.61.0 of the action corresponds to a commit with hash 8c8163ef62cf9c4677c8e800f36270af27930f42, so we might want to change our configuration as follows:

- name: Bump version and push tag

uses: anothrNick/github-tag-action@8c8163ef62cf9c4677c8e800f36270af27930f42 env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}When we use actions provided by GitHub we trust them not to mess with version tags and to thoroughly test their code.

In the case of third-party actions, the code might end up being buggy or even malicious. Even when the author of the open-source code does not have the intention of doing something bad, they might end up leaving their credentials on a post-it note in a cafe, and then who knows what might happen.

By pointing to the hash of a specific commit we can be sure that the code we use when running the workflow will not change because changing the underlying commit and its contents would also change the hash.

Keep the main branch protected

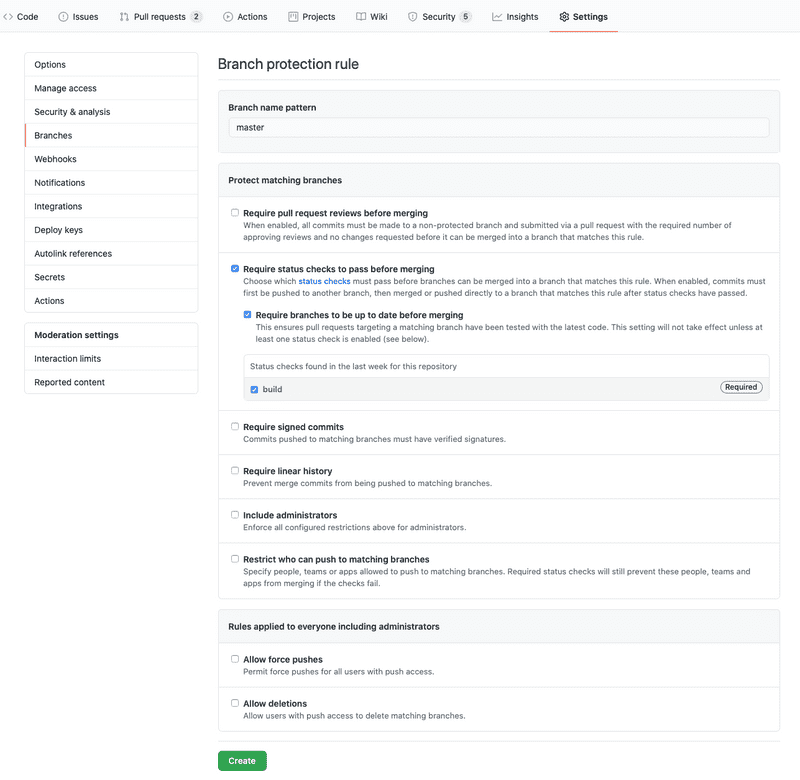

GitHub allows you to set up protected branches. It is important to protect your most important branch that should never be broken: main. In repository settings, you can choose between several levels of protection. We will not go over all of the protection options, you can learn more about them in GitHub documentation. Requiring pull request approval when merging into the main branch is one of the options we mentioned earlier.

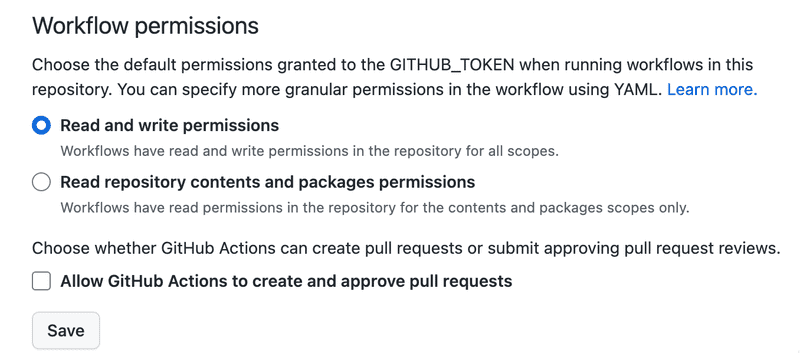

From CI point of view, the most important protection is requiring status checks to pass before a PR can be merged into the main branch. This means that if you have set up GitHub Actions to run e.g. linting and testing tasks, then until all the lint errors are fixed and all the tests pass the PR cannot be merged. Because you are the administrator of your repository, you will see an option to override the restriction. However, non-administrators will not have this option.

To set up protection for your main branch, navigate to repository "Settings" from the top menu inside the repository. In the left-side menu select "Branches". Click "Add rule" button next to "Branch protection rules". Type a branch name pattern ("main" will do nicely) and select the protection you would want to set up. At least "Require status checks to pass before merging" is necessary for you to fully utilize the power of GitHub Actions. Under it, you should also check "Require branches to be up to date before merging" and select all of the status checks that should pass before a PR can be merged.