b

Introducción a las acciones de Github

Before we start playing with GitHub Actions, let's have a look at what they are and how do they work.

GitHub Actions work on a basis of workflows. A workflow is a series of jobs that are run when a certain triggering event happens. The jobs that are run then themselves contain instructions for what GitHub Actions should do.

A typical execution of a workflow looks like this:

- Triggering event happens (for example, there is a push to the main branch).

- The workflow with that trigger is executed.

- Cleanup

Basic needs

In general, to have CI operate on a repository, we need a few things:

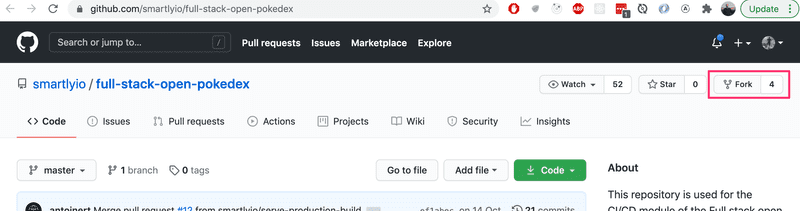

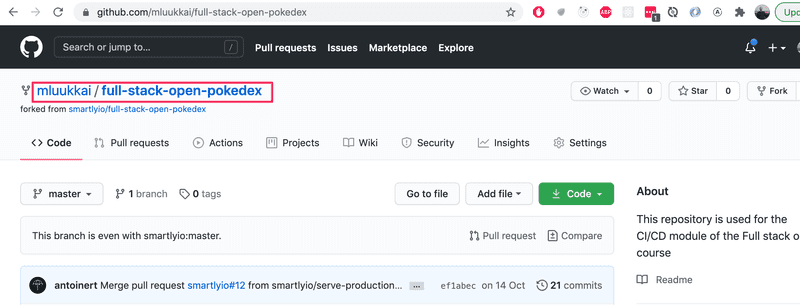

- A repository (obviously)

- Some definition of what the CI needs to do: This can be in the form of a specific file inside the repository or it can be defined in the CI system

- The CI needs to be aware that the repository (and the configuration file within it) exist

- The CI needs to be able to access the repository

- The CI needs permissions to perform the actions it is supposed to be able to do: For example, if the CI needs to be able to deploy to a production environment, it needs credentials for that environment.

That's the traditional model at least, we'll see in a minute how GitHub Actions short-circuit some of these steps or rather make it such that you don't have to worry about them!

GitHub Actions have a great advantage over self-hosted solutions: the repository is hosted with the CI provider. In other words, GitHub provides both the repository and the CI platform. This means that if we've enabled actions for a repository, GitHub is already aware of the fact that we have workflows defined and what those definitions look like.

Getting started with workflows

The core component of creating CI/CD pipelines with GitHub Actions is something called a Workflow. Workflows are process flows that you can set up in your repository to run automated tasks such as building, testing, linting, releasing, and deploying to name a few! The hierarchy of a workflow looks as follows:

Workflow

-

Job

- Step

- Step

-

Job

- Step

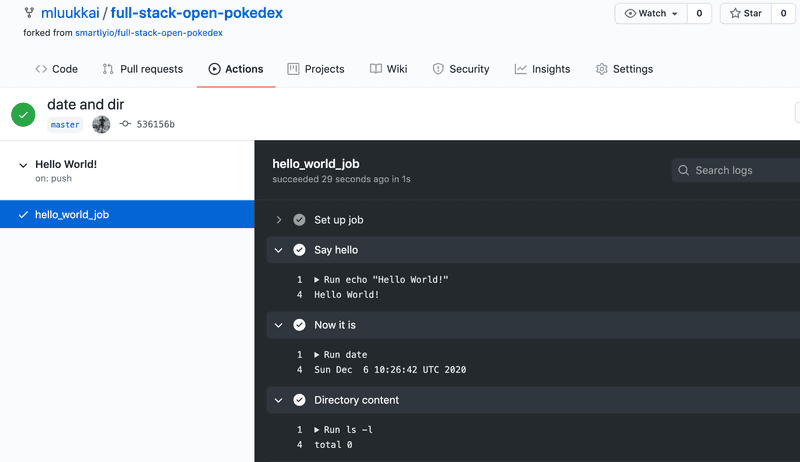

Each workflow must specify at least one Job, which contains a set of Steps to perform individual tasks. The jobs will be run in parallel and the steps in each job will be executed sequentially.

Steps can vary from running a custom command to using pre-defined actions, thus the name GitHub Actions. You can create customized actions or use any actions published by the community, which are plenty, but let's get back to that later!

For GitHub to recognize your workflows, they must be specified in .github/workflows folder in your repository. Each Workflow is its own separate file which needs to be configured using the YAML data-serialization language.

YAML is a recursive acronym for "YAML Ain't Markup Language". As the name might hint its goal is to be human-readable and it is commonly used for configuration files. You will notice below that it is indeed very easy to understand!

Notice that indentations are important in YAML. You can learn more about the syntax here.

A basic workflow contains three elements in a YAML document. These three elements are:

- name: Yep, you guessed it, the name of the workflow

- (on) triggers: The events that trigger the workflow to be executed

- jobs: The separate jobs that the workflow will execute (a basic workflow might contain only one job).

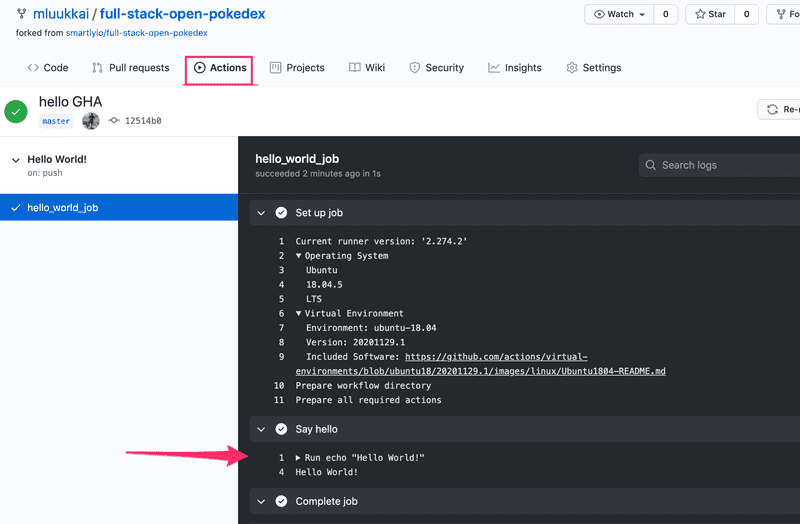

A simple workflow definition looks like this:

name: Hello World!

on:

push:

branches:

- main

jobs:

hello_world_job:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Say hello

run: |

echo "Hello World!"There is one job named hello_world_job, it will be run in a virtual environment with Ubuntu 20.04. The job has just one step named "Say hello", which will run the echo "Hello World!" command in the shell.

So you may ask, when does GitHub trigger a workflow to be started? There are plenty of options to choose from, but generally speaking, you can configure a workflow to start once:

- An event on GitHub occurs such as when someone pushes a commit to a repository or when an issue or pull request is created

- A scheduled event, that is specified using the cron-syntax, happens

- An external event occurs, for example, a command is performed in an external application such as Slack or Discord messaging app

To learn more about which events can be used to trigger workflows, please refer to GitHub Action's documentation.

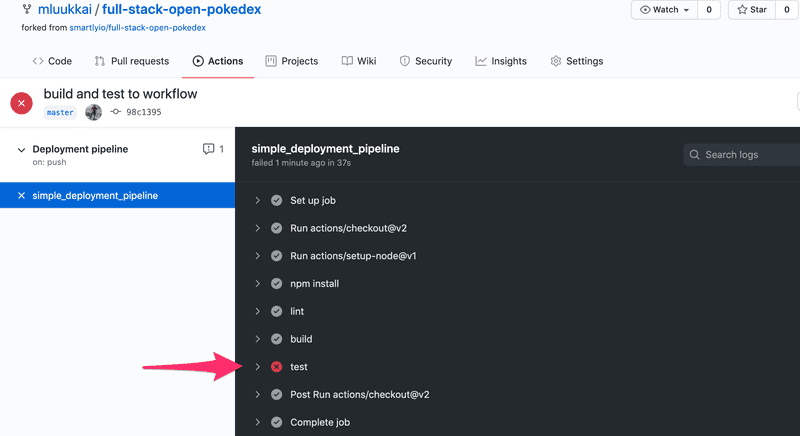

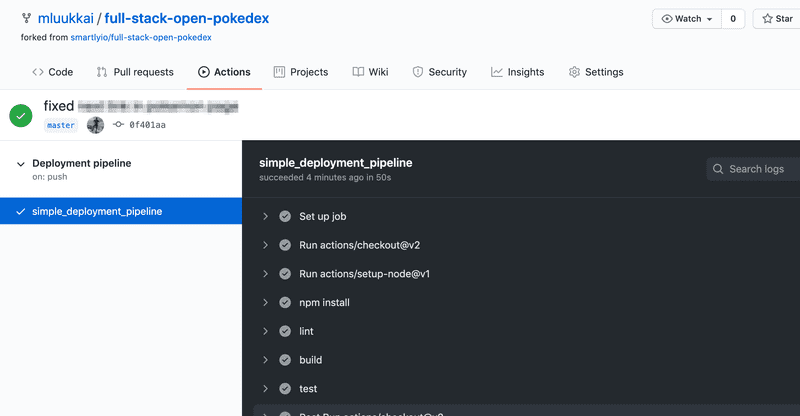

Setting up lint, test and build steps

After completing the first exercises, you should have a simple but pretty useless workflow set up. Let's make our workflow do something useful.

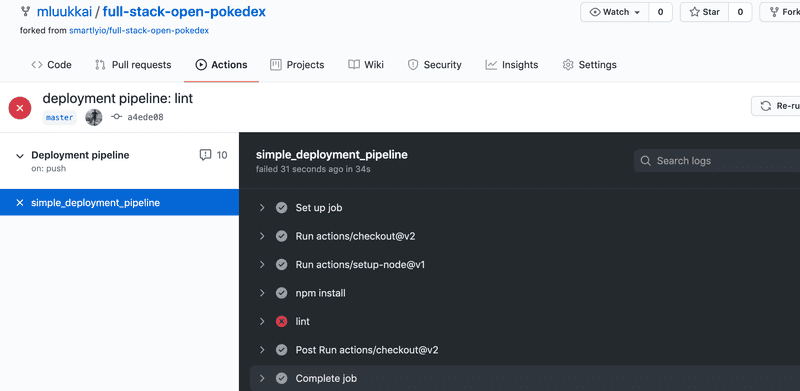

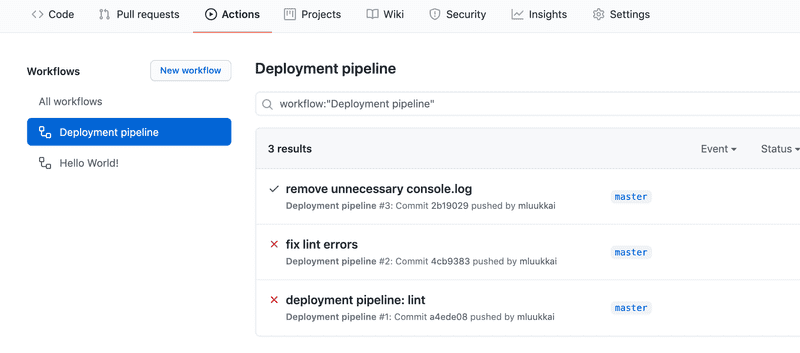

Let's implement a GitHub Action that will lint the code. If the checks don't pass, GitHub Actions will show a red status.

At the start, the workflow that we will save to file pipeline.yml looks like this:

name: Deployment pipeline

on:

push:

branches:

- main

jobs:Before we can run a command to lint the code, we have to perform a couple of actions to set up the environment of the job.

Setting up the environment

Setting up the environment is an important task while configuring a pipeline. We're going to use an ubuntu-latest virtual environment because this is the version of Ubuntu we're going to be running in production.

It is important to replicate the same environment in CI as in production as closely as possible, to avoid situations where the same code works differently in CI and production, which would effectively defeat the purpose of using CI.

Next, we list the steps in the "build" job that the CI would need to perform. As we noticed in the last exercise, by default the virtual environment does not have any code in it, so we need to checkout the code from the repository.

This is an easy step:

name: Deployment pipeline

on:

push:

branches:

- main

jobs:

simple_deployment_pipeline: runs-on: ubuntu-latest steps: - uses: actions/checkout@v4The uses keyword tells the workflow to run a specific action. An action is a reusable piece of code, like a function. Actions can be defined in your repository in a separate file or you can use the ones available in public repositories.

Here we're using a public action actions/checkout and we specify a version (@v4) to avoid potential breaking changes if the action gets updated. The checkout action does what the name implies: it checkouts the project source code from Git.

Secondly, as the application is written in JavaScript, Node.js must be set up to be able to utilize the commands that are specified in package.json. To set up Node.js, actions/setup-node action can be used. Version 20 is selected because it is the version the application is using in the production environment.

# name and trigger not shown anymore...

jobs:

simple_deployment_pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-node@v4 with: node-version: '20'As we can see, the with keyword is used to give a "parameter" to the action. Here the parameter specifies the version of Node.js we want to use.

Lastly, the dependencies of the application must be installed. Just like on your own machine we execute npm install. The steps in the job should now look something like

jobs:

simple_deployment_pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-node@v4

with:

node-version: '20'

- name: Install dependencies run: npm installNow the environment should be completely ready for the job to run actual important tasks in!

Lint

After the environment has been set up we can run all the scripts from package.json like we would on our own machine. To lint the code all you have to do is add a step to run the npm run eslint command.

jobs:

simple_deployment_pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-node@v4

with:

node-version: '20'

- name: Install dependencies

run: npm install

- name: Check style run: npm run eslintNote that the name of a step is optional, if you define a step as follows

- run: npm run eslintthe command that is run is used as the default name.